Visual Agnosia

In ‘The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat,’ Oliver Sacks presented to the world the case of Dr. P, a man whose visual agnosia meant he could only focus on one individual feature of someone’s face. “His eyes would dart from one thing to another, picking up tiny features, individual features, as they had done with my face. A striking brightness, a colour, a shape would arrest his attention and elicit comment—but in no case did he get the scene-as-a-whole.”

He had no sense whatever of a landscape or scene.”

The story goes that when Dr. P saw his wife, he focused on the top of her head, unable to distinguish the context, which led to him thinking that he was looking at a hat stand. “He failed to see the whole, seeing only details, which he spotted like blips on a radar screen. He never entered into relation with the picture as a whole—never faced, so to speak, its physiognomy. He had no sense whatever of a landscape or scene.”

I often think that some poker players, myself included, have a particular type of visual agnosia. Not for faces, mind you. Ours is a sort of tunnel vision, a narrowing of the ocular spectrum, an inability to recognize the true objectives.

PokerPro2023

In the game PokerPro2023 on the Super Nintendo or whatever console the cool kids are using today, the actual game of poker is only a small part. Of course, it’s a very important part but it is just one component, one facet of a multi-faceted game that requires you to treat what you do as a business.

Running a successful shop is not just about the transactions at the till. It’s about choosing your location and opening hours, selecting the brands you will carry, and keeping the shelves stocked. Similarly, the poker pro chooses his card room and hours of work, selecting his game type and stakes. Success for both will hugely depend on these decisions.

There is also the personal management aspect. The poker pro is a human being who has good days and bad days, sharp days and dull days, lucky days and unlucky days. Combine an environment with a lot of variance with cognitive biases and you have a recipe for volatility and the reinforcement of errors. Managing yourself through a tumultuous period is key.

The scene-as-a-whole

Poker is tougher now than ever before. It used to be a game of aggression and brute force, of high c-bet percentages and barreling. Now it’s a game of mathematical exactitude and equilibrium, of calibrated betting frequencies and precise sizings. Balance is vital, both on and off the table.

It’s easy to lose sight of this but the money isn’t just a tool, a scoreboard, or a number on a screen. It has a concrete relationship with the world off the felt and, perhaps most importantly, it has a decreasing utility the more of it you accumulate. Every chip lost is more valuable than every chip gained.

Don’t be the man who mistook his life for a game

If you’re lucky enough to make money from the game, use that money to make your life better. Don’t blow it on stupid things. Spend it on something or someone you love. Respect that money because it being in your pocket means someone else had to lose it. Try your best not to lose sight of the bigger picture. Recognize the scene-as-a-whole. Don’t be the man who mistook his life for a game.

No time for anything inessential

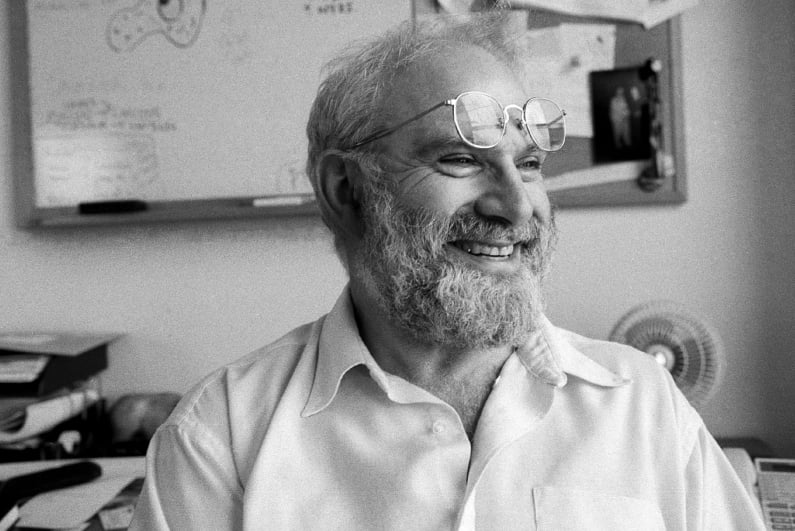

The “poet laureate of contemporary medicine,” as he was so fittingly called in the New York Times, Oliver Sacks passed away on this day eight years ago. He spent his life exploring the mysterious, complex, and extraordinary things that happen inside our heads and his clinical work inspired films, documentaries, stage plays, and an opera.

Sacks received his terminal diagnosis five months prior to his passing and from that moment he was determined to make the most of the time he had left. In a beautiful op-ed entitled, ‘My Own Life,’ he reflected on his life and proximity to death with words that were both poignant and heartening:

“Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts. This does not mean I am finished with life. On the contrary, I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight. This will involve audacity, clarity, and plain speaking; trying to straighten my accounts with the world. But there will be time, too, for some fun (and even some silliness, as well). I feel a sudden clear focus and perspective. There is no time for anything inessential.”